Brown-headed Cowbird

General Description

The Brown-headed Cowbird is well known--and widely disliked--for its practice of laying eggs in the nests of other species. Males are black birds with dull brown heads. Adult males are shiny black, while first-year males are duller black. Females are much smaller and solid brown with a whitish throat and light streaking on their undersides. Juveniles look similar to females, but are more heavily streaked with lighter bellies and light edging on their wing feathers. Cowbirds have more finch-like conical beaks than other blackbirds.

Habitat

Brown-headed Cowbirds forage in open areas and breed in open woodlands or scattered trees, so they are most common at edge areas where they can be close to both types of habitat. They are particularly common in streamside thickets and woods adjacent to agricultural fields, although they can be found in most habitats with the exception of the forest interior. Historically, they inhabited short-grass prairies, but with development, agriculture, and forest fragmentation, they have been able to expand their range significantly and now prefer human-modified habitats.

Behavior

Historically, Brown-headed Cowbirds probably followed herds of bison, walking behind them to take advantage of food kicked up in the bison's wake. Now they follow cattle and other large grazers in much the same way. They almost always forage on the ground, but also lurk about in trees and bushes, mostly watching quietly for nests to parasitize.

Diet

During the summer, about half of the Brown-headed Cowbirds' diet is made up of seeds, and the other half consists of insects and other invertebrates. Their winter diet is made up of more than 90% seeds and waste grain. Females also eat eggshells from the nests where they lay their eggs and mollusk shells, especially during the breeding season. This practice may provide the calcium they need to produce the large number of eggs they lay.

Nesting

Brown-headed Cowbirds have unusual breeding behavior: they never build nests or raise their own young. Males typically arrive on the breeding grounds before the females. Pairs are generally monogamous. Females lay eggs in other birds' nests and leave the rearing to other species. They find nests to parasitize by looking for birds building nests, either by walking along the ground, perching quietly in shrubs or trees, or making noisy flights back and forth, possibly to flush potential hosts. The female generally chooses an open cup-nest to parasitize, and usually lays one egg per nest. She waits to lay the egg until the host bird has at least one egg in its nest, and often removes one egg from the nest before laying her own. She continues the process over a period of about a month and can lay up to 40 eggs a season. Incubation time is short, 10 to 12 days, which allows the young cowbird to get a head start in the nest. Young cowbirds grow rapidly, giving them a competitive advantage over the other young in the nest. Young cowbirds usually leave the nest after 8 to 13 days, but are not fully independent from the hosts until they are about 25 to 39 days old. Then they typically form small flocks with other juveniles. Over 220 species have been observed with Brown-headed Cowbird eggs in their nests, and at least 144 species have raised Brown-headed Cowbird young to the fledgling stage, often at the expense of their own young.

Migration Status

Brown-headed Cowbirds are typically short- to medium-distance migrants, but may be present year-round in some parts of their range, including eastern Washington feedlots. In western Washington, huge numbers are seen in the Kent area (King County). They often migrate in flocks with other blackbird species.

Conservation Status

Brown-headed Cowbirds are presently far more abundant and widespread in North America than they were historically. They are relative newcomers to Washington. Although they may have been in the state in small numbers, they are generally considered to have arrived in the Columbia Basin in the late 1800s, and were regularly seen in western Washington by 1955. By 1958 they were breeding in western Washington. Development and forest fragmentation have allowed Brown-headed Cowbirds to enter new areas and exploit new host-species. A cowbird in the nest typically means less food for the host's young, as the cowbird chick is larger and more demanding. Some, or all, of the host's own young usually die as a result of lack of resources. This has had a significant impact on some species that are common cowbird hosts. Some species, including Cedar Waxwings, Gray Catbirds, Bullock's Orioles, American Robins, and jays actually recognize and eject cowbird eggs when they appear in their nests. They might instead build a new nest over the top of the old one with the cowbird egg. Many other species are not so fortunate and Brown-headed Cowbirds are considered one of the most important causes of Songbird decline in North America. The Yellow Warbler and the Song Sparrow are the two most often parasitized species in the United States. There has been a significant decline in the cowbird population in Washington between 1966 and 2002, although they are still common and widespread.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Brown-headed Cowbirds are generally summer residents in appropriate habitat throughout Washington, arriving in mid-April. Most leave by September, but some may overwinter in the Puget Trough. You can typically find them at feedlots with flocks of other blackbirds, in coastal areas, or along the Columbia River east of the Cascades.

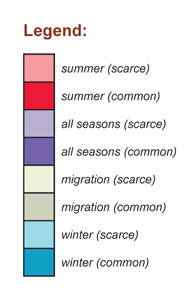

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | R | U | C | C | C | C | C | F | U | R | R |

| Puget Trough | U | U | U | C | C | C | C | F | F | F | U | U |

| North Cascades | R | R | R | F | C | C | C | C | R | R | R | R |

| West Cascades | R | R | R | U | C | C | C | C | F | U | R | R |

| East Cascades | R | R | R | U | C | C | C | C | C | U | R | R |

| Okanogan | U | C | C | C | ||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | F | F | F | F | F | |||||||

| Blue Mountains | R | F | C | C | C | C | U | R | ||||

| Columbia Plateau | U | U | U | C | C | C | C | U | U | U | U | U |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

BobolinkDolichonyx oryzivorus

BobolinkDolichonyx oryzivorus Red-winged BlackbirdAgelaius phoeniceus

Red-winged BlackbirdAgelaius phoeniceus Tricolored BlackbirdAgelaius tricolor

Tricolored BlackbirdAgelaius tricolor Western MeadowlarkSturnella neglecta

Western MeadowlarkSturnella neglecta Yellow-headed BlackbirdXanthocephalus xanthocephalus

Yellow-headed BlackbirdXanthocephalus xanthocephalus Rusty BlackbirdEuphagus carolinus

Rusty BlackbirdEuphagus carolinus Brewer's BlackbirdEuphagus cyanocephalus

Brewer's BlackbirdEuphagus cyanocephalus Common GrackleQuiscalus quiscula

Common GrackleQuiscalus quiscula Great-tailed GrackleQuiscalus mexicanus

Great-tailed GrackleQuiscalus mexicanus Brown-headed CowbirdMolothrus ater

Brown-headed CowbirdMolothrus ater Orchard OrioleIcterus spurius

Orchard OrioleIcterus spurius Hooded OrioleIcterus cucullatus

Hooded OrioleIcterus cucullatus Bullock's OrioleIcterus bullockii

Bullock's OrioleIcterus bullockii Baltimore OrioleIcterus galbula

Baltimore OrioleIcterus galbula Scott's OrioleIcterus parisorum

Scott's OrioleIcterus parisorum